Societal shift in carbohydrate, fat and protein intake behind overfat epidemic.

Among the many problems with the diet trend of the past 50 years is that it has dulled our senses about what we should eat. Calories, most believe, are the enemy, and since fat has twice the calories of carbohydrates, it must be “bad,” too.

Obviously, this is untrue, but it has led to many millions of people becoming overfat and unhealthy. Unfortunately, marketing is often more powerful than science.

We have become obsessed with calories in particular, despite the fact that the long-term success of calorie-counting diets have been shown to be a dismal failure. Studies show people who follow them for three to five years actually gain weight.

Since 1960, the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) has analyzed the food intakes of large numbers of people. The overfat epidemic has been growing steadily during this same period, and since the mid-1970s it took a sudden turn for the worse. Along with the growth in the overfat epidemic, rates of obesity also paralleled other conditions of poor health, including diabetes and other problems that are now part of the metabolic syndrome. This includes many physical injuries, aches and pains associated with inflammation in joints, ligaments and muscles.

During these epidemics, the NHANES study found that caloric intake has increased, and that these increases have been due almost entirely to people eating more refined carbohydrates.

The food we eat plays a more important role in overall health than does fitness and exercise. Another unhealthy trend is the misinformation — promoted by companies selling refined carbohydrates and governments influenced by lobbyists — that the overfat epidemic is due to reduced levels of activity, and that it’s OK to eat junk food as long as you exercise. As we now know, we can’t run away from a bad diet.

Studies show that physical activity levels have basically changed little during this period of the overfat epidemic. What has changed is fitness. While athletic performance records continue to be broken by a handful of individuals, average race times today, for example, are slower. The American Heart Association has shown that many children can’t run as far or fast as their parents did. In fact, in a one-mile run, today’s children are about a minute and a half slower than their peers 30 years ago with average changes similar between boys and girls, younger and older kids. This serious problem may also reflect increased carbohydrate intake.

While low-fat foods sometimes appear to make sense to prevent higher levels of body fat, it’s actually metabolically illogical. That’s because low-fat meals usually mean increased consumption of refined carbohydrates, which produce the proverbial three-strikes and you’re out: Up to half of these carbs turn to fat and go into storage. They also reduce our ability to burn body fat for energy, and they impair aerobic fitness. These effects are immediate.

The NHANES study found that the increased consumption of carbohydrates from 1974 to 2000 was significant. In men, it rose from about 40 percent to almost 50 percent of total calories, and in women, carbohydrate intake rose from 45 percent to 52 percent. Fat intake actually decreased for men during this period, and slightly increased for women, despite women being more prone to go on low-cal/low-fat diets.

This data was also confirmed in a 2013 study by the USDA.

During my years in private practice, within the NHANES study period noted above, I performed at least one dietary analysis on virtually all patients. The same trend was evident. By 1981 I found myself recommending a diet that was no more than a moderate 40 percent natural carbohydrates like fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grains, and avoiding avoiding all refined carbs such as breads and pasta, which gave me the reputation as the “low-carb guy.” However, this level was obviously low only in relation to those consuming 50, 60, 70 percent or more of their food as carbohydrate, most of which was refined. For older individuals who tend to become more carbohydrate intolerant, less was recommended, as low as 20 percent (and sometimes less to stimulate ketosis in appropriate patients). But what is “low” or “high” carbohydrate?

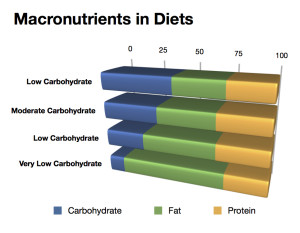

The developing consensus, without adjusting for an individual’s specific needs, is listed below. I can agree with this, however, if the amount of carbohydrate is based on natural forms and not refined.

- High carb diet: >45 percent (this would leave about 30 percent for fat and 25 percent for protein).

- Moderate carb diet: 26-45 percent (leaving roughly 35 percent fat and 30 percent protein).

- Low carb diet: 25 percent (leaving about 45 percent fat and 30 percent protein).

- Very low carb (ketogenic) diet: 10 percent (leaving about 65 percent fat and 25 percent protein).

Two important points:

- There is no minimum daily requirement for carbohydrates (unlike fat and protein).

- For very low-carb/ketogenic diet, most individuals require between 30-50 grams of carbs and may have to reduce protein to 20 percent.

Since government agencies won’t make the necessary recommendations to reverse the overconsumption of carbohydrates that have caused an overfat epidemic, along with rising disease states, individuals will have to take responsibility for their own health by making these important adjustments and implement healthy eating.

Dr. Phil Maffetone