After seven decades of bad nutritional advice, let a new era of balanced and healthy eating begin.

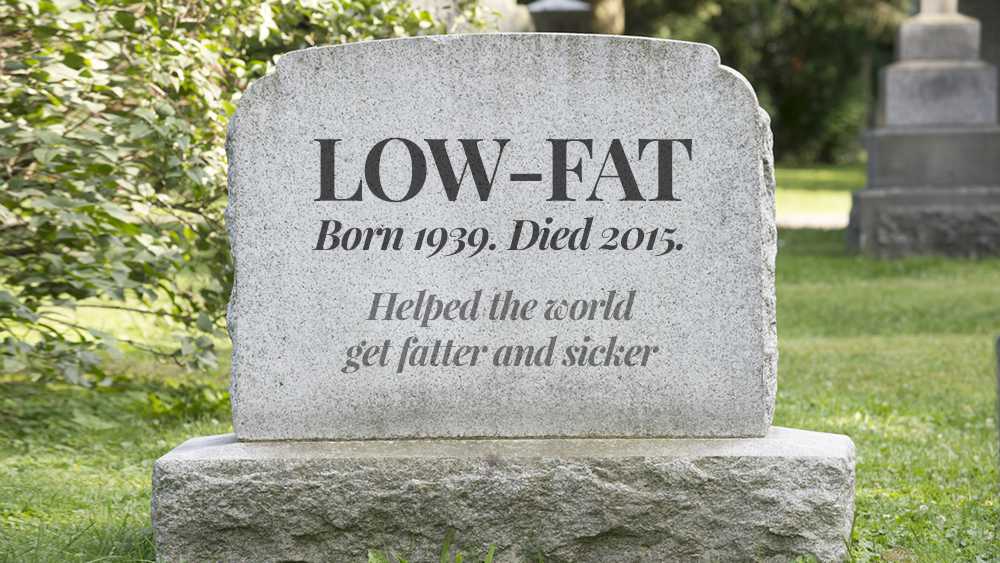

The year 2015 may someday be found on a historical timeline of dietary fads as the year Low-Fat finally died. Which particular day will be celebrated is, of course, up to Hallmark, who will promote cute traditional and e-cards with sayings like:

“Eat Fat to Get Slim.”

The actual day may have been when a carefully constructed comment, almost an aside in the 2015 USDA nutrition guidelines, removed the upper limit on dietary fat with the claim, “Reducing total fat (which really means replacing total fat with overall carbohydrates) does not lower cardiovascular disease risk,” adding that people should be “optimizing types of dietary fat and not reducing total fat.”

Or, the particular day could have been when that most mainstream of traditional medical journals, The Journal of the American Medical Association, printed a comment about the new recommendations as it “tacitly acknowledges the lack of convincing evidence to recommend low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets for the general public in the prevention or treatment of any major health outcome, including heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, or obesity.”

The JAMA article’s author, Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, dean of Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition, wrote, “We really need to sing it from the rooftops that the low-fat diet concept is dead, there are no health benefits to it.”

Some of us have been singing this very song from those rooftops for quite some time, and have been considered nuts, fanatics or added to the official quack list. For instance, I’ve talked, written, pleaded and addressed the nutritional importance of dietary fats my entire adult life.

Natural fat newbies should be reminded that, scientifically, the essentiality of fat was discovered in 1929. (Nobody agrees on the exact birth date of Low-Fat, but it possibly had its beginnings in The Rice Diet founded in 1939 by Dr. Walter Kempner.)

How did Low-Fat die? Perhaps it was the yellow yolks, once thought to clog our arteries from merely thinking about them, that triggered the killing softly of low-fat. After decades of trashing eggs and cholesterol because of “conclusive studies” that showed eating them was harmful, in 2015 the U.S. government quietly said there is no evidence eating any amount of cholesterol is unhealthy. Now there’s egg on their faces.

Whatever day it was, suddenly the war on fat is over, and fat is now our official friend.

But now what? Now that fat is our friend, and we are equipped with the knowledge about bad fats — omega-6 oils and trans fat in particular — what do we do now? The answer is simple. People have to get fat phobia out of their minds, a change that’s difficult to make. The idea of a big beautiful glob of great tasting healthy sour cream on top of a bowl of chili, an extra couple of tablespoons of olive oil on a salad, or heavy cream, coconut oil and an egg yolk blended into your morning coffee may be intellectually OK, but for many the mind is just not willing to let go — there’s still that voice of the little misguided gremlin saying “once on the lips forever on the hips.”

One lingering problem regarding fat involves sugar. We can, in fact, put more stored fat on our body from eating even relatively small amounts of refined carbohydrates. This will also prevent body fat from being burned for energy, helping to maintain too much stored fat. With 75 percent of the world being overfat, this remains a huge health problem, not to mention a serious concern for our economy.

Another lingering problem is the misguided calories-in, calories-out idea still echoing in our minds. It’s a reflex for too many people who are trying to get rid of their excess body fat. This long-held notion should also be thrown out because it helps maintain fat phobia — people think of fat as a high-calorie macronutrient (which it is) rather than a source of high potential energy.

Of course, many of these problems remain in our culture because “diets” themselves are still popular. Books, magazine articles, internet buzz and other reminders about the latest fad diet won’t die too soon because there is so much money to be made in it.

Long ago I noticed that when people made the decision to eat better, reducing carbohydrate may have been difficult, but eating more fat was actually mentally tortuous for them because they had been conditioned to think of it as unhealthy. You can’t do one without the other. Think of a see-saw with protein in the middle, and carbohydrate and fat at either end. As we reduce carbohydrates we must increase fat.

This problem is a common one during the Two-Week Test. One of the main reasons some people don’t feel right is that carbohydrates are reduced and fat is not sufficiently increased. The lack of calories, especially in athletes, can be an obvious problem.