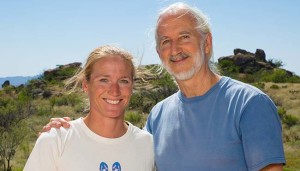

Triathlete and doctor Amanda Stevens gets her groove back when muscle abnormalities are identified and corrected.

Dr. Phil Maffetone is well-known for coaching methods such as training slow to race fast. Many also know him as the longstanding nutrition guru who says avoid all junk food and eat healthy fats and protein.

Only a few know about the other part of his career, which also involved athletes — hands-on therapy. It’s why successful professional athletes like Mark Allen and Stu Mittleman, as well as teams from various sports, have brought Phil to their important events to fine-tune their bodies.

While Phil is no longer in private practice, he does work with an exclusive handful of athletes. He recommends others seek out a healthcare professional to help assess and treat problems. (MAF will be creating a list of recommended healthcare professionals and coaches for referral in the future.)

“The goal,” says Phil, “is to evaluate muscle balance, uncover abnormalities, and correct them.” By doing so, he says mechanical improvements are quickly realized and better movement economy leads to faster paces.

“For me, this is as much a part of coaching, as training, nutrition and other aspects of human performance,” he says. “In fact, they all work together.”

Evaluation includes a good performance history — answers to questions such as how do you feel on the bike after an hour or two? Which areas don’t feel normal, which feel weak? Do you have pain or energy patterns where there are lows and highs? These and other questions apply to both training and racing. Every answer is an important piece of information, which is combined with other findings.

Dr. Amanda Stevens is a professional triathlete and medical doctor. She started working with Phil last year. Before that time, she acquired the latest technology in power meters — Pioneer’s Power Meter System, which can measure watts in the left and right side separately.

“I was excited to see this new technology because it can serve as an important assessment tool to measure body balance,” says Phil. “It’s important to measure human performance, the reason I use heart rate. But observation of gait in runners, posture on the bike, swim mechanics, and other movements are just as important to assess.”

He says the advent of power meters provides another way to measure performance. Instead of using miles or kilometers per hour at a given MAF (submax) heart rate, the new equipment measures wattage output and gives the ability to observe power balance.

Phil has evaluated cyclists in a wind tunnel, on stationary devices in his clinic, and spent many hours watching athletes out on their road bikes.

“Observation before and after therapy also has great value,” he says, “helping to assess whether the treatment has actually accomplished anything as indicated by better performance and improved posture and gait.”

Phil says devices that measure left and right power output now make biomechanical evaluation even easier. Along with other factors, looking at the power numbers before and after treatment is of great value.

On their first meeting, Phil evaluated Amanda from the feet up and head down, starting with standing and sitting posture.

Even when lying down, postural deviation is meaningful.

In many ways, these postures reflect biomechanical performance on the bike. A head that’s tilted or rotated abnormally, even a small amount, will probably be that way on the bike, and have a negative impact on movement economy. Changing a cyclist’s posture changes many things, including one’s relationship with the bike itself. In many cases, making a mechanical change in the body will require an appropriate and precise change in the bike setup.

The hard part is uncovering these muscle imbalances and determining which are primary and don’t hurt — but are the ones to treat — and which are secondary and often symptomatic, but don’t need treatment. Once that is determined, fixing imbalances is easy for a skilled practitioner.

At her first meeting with Phil, Amanda already was aware of her muscle imbalances. “For the past year or so, my left leg felt ‘dead’ and seemed to lag behind. I would have to mentally coach it to get a small response from it. I felt very unbalanced and had little control over the whole left side.”

This was easily demonstrated on the new technology as a significant imbalance — 60 percent of power was going through the right foot, and only 40 percent on the left. This is a good example of poor economy.

Based on early assessments, Phil evaluated a variety of muscles and found a weakness in the left quadriceps (specifically, the vastus group). This was associated with a tight hamstring group.

“Muscle imbalance usually involves an inhibited, or “weak” muscle or group of muscles that is primary, and a secondary one that is too tight,” he says.

This would contribute to Amanda’s significant imbalance in power output between left and right side. The assessment process continued.

It may seem counter-intuitive, but Phil says the most misunderstood muscles in endurance athletes (and non-athletes as well) are those in the head and neck. While many people think the quads, hamstrings and foot muscles are key, muscles higher up control whole body balance and are typically a more primary and often a hidden problem. These include the neck flexor muscles (front of neck), those that open and close the jaw joint, and the upper trapezius on either side of the head, neck and shoulder.

Muscle testing revealed a problem with Amanda’s left upper trapezius. Correcting this muscle imbalance using manual biofeedback was the first step and secondary muscle imbalances also improved quickly.

Amanda was amazed with the results.

“The next morning I went out to ride with no expectations. The minute I got on my bike, I felt different and good!” she says. “My left leg was functioning better and without thought. The left and right sides felt more balanced than ever.”

And the power meter provided definitive proof — the left was about 49 percent and the right 51.

After another evaluation and treatment, with additional improvement in riding, something still was not quite right. The remedy was simple: getting a better bike fit for Amanda’s newly balanced body.

“This was a huge step forward. I was finally able to start riding a bike the way it was meant to be ridden,” Amanda says. “I was able to relax my shoulders, which helped open up and loosen my hips, and riding became much more efficient and consistent. I felt like I started to absorb the training better and also recover a little quicker.”

Phil had seen this too many times before to be surprised.

“Just the awareness of the muscles and how they work helps balance the whole body,” he says. “This is important for the brain to better control muscle contractions and relaxations.”

“I can use all my muscles in concert and correctly,” Amanda says. “My left knee would collapse inward and I couldn’t get it working even when trying to rotate it outward with other muscles. Now things feel balanced, even my core, deep abdominal and latissimus and lower traps work well.”

Phil says athletes often try to consciously compensate for mechanical problems, which is almost impossible to do well and could lead to other injuries, and Amanda was no different.

“Getting balanced from the top down means the feet work better too — an obvious need as that’s the body’s power that goes into the pedal,” he says.

Amanda says her entire body now feels stable from the foot up. “I’m now able to ride with more power at the same heart rate,” she says.

At age 38, she wants to keep pace with the younger stars of the sport, and wants any healthy advantage she can attain to improve fitness.

Phil notes that as we age, it takes a bit longer to recover, and we don’t compensate as fast. “When we’re 20 years old, imbalances often don’t hurt as much, and are compensated for really well by a healthy body.

With Amanda’s muscle imbalances corrected, both she and Phil expect the wattage output to increase at that same heart rate through the summer leading up to the Ironman World Championships in Kona, Hawaii, in October.

Amanda’s first three races this year were in June. She placed third in the St. Croix triathlon on the way to Brazil Ironman, where she also placed third, and had an Ironman PR by 4 minutes and run/marathon PR by 7 minutes. More recently, she placed 2nd at the Ironman Coeur d’Alene in Idaho on June 28.

By Hal Walter

Senior Editor