Still confused about blood pressure? So is the healthcare profession. Are meds the real solution? Or is it time to treat the actual cause?

Since the latest guidelines on blood pressure were released, many patients have been treated aggressively, using drugs to reduce systolic BP to less than 130 mmHg. However, some patients are treated even more aggressively, attempting to lower systolic BP to under 120. This continues to be a real concern.

Meanwhile, as more people are being put on meds, the root cause of hypertension — very often linked to carbohydrate intolerance — goes unaddressed. Other potential causes of of high blood pressure also can be easily addressed more conservatively as well.

What are the guidelines?

The newest guidelines lowered the range of “healthy” blood pressures, in effect putting tens of millions more people on meds worldwide. Yet, current guidelines for the systolic blood-pressure target remain inconsistent. They range from under 150 mm Hg set by the American College of Physicians – American Academy of Family Physicians, to less than 130 recommended by the American College of Cardiology – American Heart Association. Some studies show that cardiovascular risk is further reduced with intensive blood-pressure control to below 120. Other studies show that reducing systolic blood pressure to less than 130 should be done with caution due to potential side-effects.

Clearly, hypertension is a common and serious problem that can significantly raise cardiovascular risk (primarily stroke, coronary heart disease, and kidney disease). However, it’s not really that simple. In a The New England Journal of Medicine editorial, Dr. Mark Nelson states that, “we continue to manage blood pressure as an isolated risk factor rather than as an integrated part of a patient’s risk profile because we adhere to the rusted-on clinical concept of hypertension. According to this concept, there is an arbitrary number above which disease is present and below which it is absent.”

In other words, he’s saying we should look at the individual, and the big picture, and consider hypertension as a risk factor, but not a disease itself.

As there is no definitive BP number indicative of disease, some researchers say this makes the definition of hypertension arbitrary (in particular, when no symptoms exist). Moreover, many people do not have their BP taken accurately.

There’s no question that the appropriate medication plan — often more than one med is prescribed — can reduce blood pressure and lower cardiovascular risks. However, other important questions include just how much it should be reduced, whether it influences health significantly, cost effectiveness, and how it affects quality of life.

Consider that there’s a drawback. While cardiovascular risk is reduced, the risk of death may be no different in those whose BP is more aggressively treated. The risk-reward factor is something to consider: Does an individual gain sufficient benefits that outweigh the side-effects? While medication studies evaluate relatively short-term health effects, other important factors such as long-term health outcomes, quality of life, and cost effectiveness must also be considered.

Side-effects of meds

Elevated BP is sometimes a normal response to poor circulation, such as arterial stiffness. Reducing BP too much, for example in a patient with narrowed arteries who needs to get blood flow to important areas of the body, such as the brain, can also impair function in those areas (especially the brain). Relative hypotension is a side-effect which can further cause other abnormalities such as myocardial ischemia and stroke, and increased risk of kidney injury.

While there are many well-known side-effects of the various medications used to treat high blood pressure, the real serious one is avoiding the condition that caused hypertension.

Cause and effect

Numerous problems can promote hypertension. We know what the more common ones are, but what’s important is to prioritize them. Here are some examples:

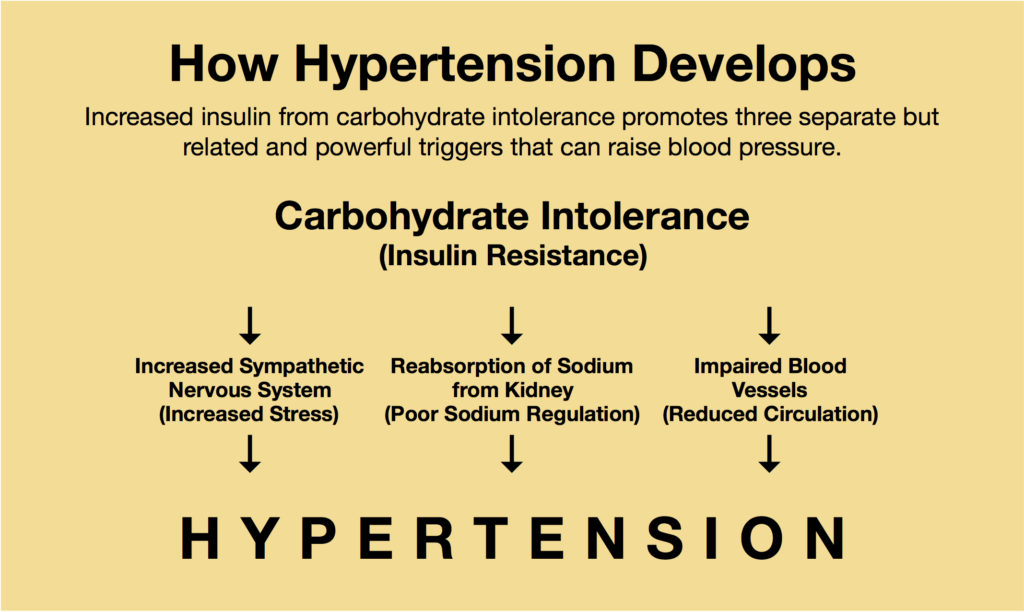

- Excess stress increases the sympathetic nervous system, which can constrict blood vessels and raise blood pressure. Some conservative measures that attempt to address this include meditation, yoga, massage, and other relaxation techniques.

- Blood vessels can also become narrow due to plaque, impairing circulation. As noted above, narrowing of the arteries can also increase blood pressure to restore or maintain normal circulation.

- Kidney dysfunction can raise blood pressure by reabsorbing sodium that would normally be eliminated by the body through urine. (Salt-restriction can sometimes lower the body’s sodium and reduce blood pressure a certain amount.

- Excess insulin, associated with insulin resistance — carbohydrate intolerance, or CI — can promote all the above. This includes impaired blood sugar regulation, a hallmark of CI. (Those with more developed anaerobic system and fast-twitch muscle fibers tend to also have many of the above factors.) This makes CI a primary cause of hypertension through one or more mechanisms. (Addressing CI though dietary modification is addressed below.)

- While age is often blamed for high BP, it is associated with hypertension but not a cause. While hypertension typically increases with age, it parallels increasing CI, rising insulin levels and blood sugar abnormalities, which can promote hypertension.

(In addition to hypertension, any or all these health problems can promote other abnormal signs and symptoms as well and are discussed throughout this website.)

Carbohydrate intolerance, then, may be the most primary cause of most hypertension. The graphic below summarizes these mechanisms and shows how hypertension typically develops.

Young Hypertension

While CI worsens with age, even young people now develop hypertension, with one or more of the above conditions. Sadly, unhealthy children are a rapidly growing population of hypertensive patients. They are the next generation of unhealthy adults.

Just like type 2 diabetes, once only found in adults, insulin resistance, hypertension, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and other cardiometabolic derangements are now becoming common in children. This corresponds with this data:

- About 70 percent of U.S. children are overfat (with high rates globally).

- Over 90 percent of meals eaten by U.S. children consists of junk food (with high rates globally).

The good news is that these children respond exceptionally well and very rapidly to better eating.

Alternative Remedies

Common attempts at non-drug remedies for hypertension abound. From relaxation and meditation, various vitamins and minerals, different types of exercise, and many others. In those sensitive to sodium (not all hypertensives are), sodium restriction can also help reduce blood pressure. However, it does not treat the cause of the body’s impaired sodium regulation (which keep reabsorbing sodium the body wants to eliminate).

Overall, while these remedies can sometimes help, they usually don’t address the cause — carbohydrate intolerance — so long-term correction is usually not obtained.

Addressing the Cause

Reducing excess insulin, and insulin resistance, e.g., improving carbohydrate metabolism, typically reduces high BP. For decades, I have seen the Two-Week Test, which reduces CI, reduce BP very quickly — it actually is so effective and can occur so quickly that individuals with hypertension who are on medication are alerted to carefully monitor their BP during the Test to avoid against BP lowering too much. (In most cases, their health practitioners would adjust or eliminate meds as necessary.)

Reducing BP is not the only benefit of the Two-Week Test — it can not only reduce cardiovascular risk, but metabolic risk as well (those associated with diabetes, excess body fat, hormone imbalance, and others).

While rates of hypertension are on the increase, much of this can be attributed to changing guidelines. For many, conservative, natural remedies may be a viable solution to medications.

Related link

Three levels of blood pressure risk

References

Jackson R, et al. Management of raised blood pressure in New Zealand: a discussion document.

BMJ. 1993; 307(6896). doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6896.107,

Jung CE, et al. Relationship among Age, Insulin Resistance, and Blood Pressure. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017; 11(6). doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2017.04.005.

Nelson MR. Moving the Goalposts for Blood Pressure — Time to Act. N Engl J Med. 2021. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMe2112992.

Zhang W, et al. Trial of Intensive Blood-Pressure Control in Older Patients with Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2111437.