Many mechanical problems are a question of balance rather than of physical strength vs. weakness. Even biochemical and mental stresses can be affected by muscles.

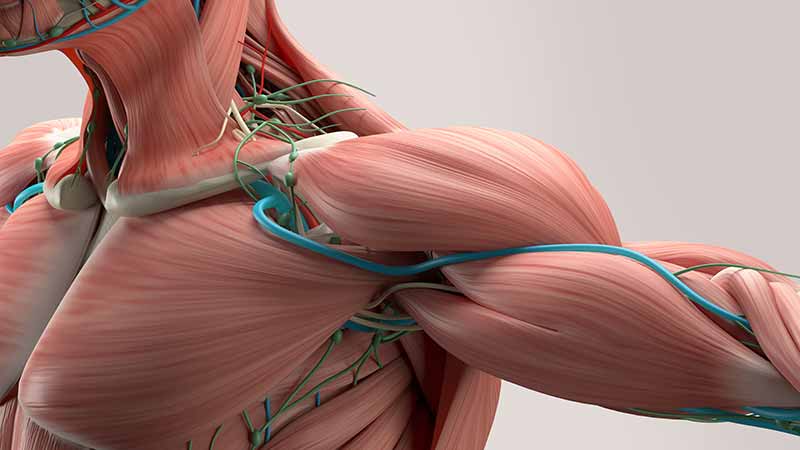

Though the muscular system is often the most visible, it is also one of the more overlooked networks of the human body. Clearly muscles are responsible for our physical abilities to move objects or get from one place to the other, but they also house key components of the metabolism — the body generates energy from fat and sugar within the muscles. Muscles even have a corresponding relationship to our biochemical and mental state, especially when pain is a part of the problem.

While many people have joined the ranks of healthy eating and exercise, knowledge about muscles, their overall place in health and fitness, and their evaluation and treatment when there are problems, often lags behind.

We tend to limit our image of muscles as strong vs. weak, or sometimes large vs. small, but there’s much more to this issue than that. Over the past 100 years our understanding of the muscular system has quietly evolved to include the concept of muscle imbalance, how to evaluate it, and ways to correct it.

For many people the first sign of a muscle imbalance is joint or muscle pain, or an isolated feeling of weakness. In extreme cases a muscle may simply fail in the course of an activity — for example a runner may suddenly and temporarily lose muscular control in the lower leg. These symptoms can all be treated ahead of these downstream symptoms after assessing the location and cause of the muscle imbalance.

Muscle Imbalance

While there are several schools of thought regarding the neurophysiology of muscle imbalance, there is one common idea — muscle imbalance consists of two or more opposing muscles, one being overactive or too tight and the other underactive or too loose.

Clinically, two categories of people have muscle imbalance. In one case, muscles can become too overdeveloped, or underdeveloped due to over- or under-use. An example of the former is through weight-lifting or other physical work, when some muscles become overbulked or too strong, relative to others. Proper technique can prevent and correct this problem. Muscle underdevelopment, on the other hand, usually due to lack of use, aging or chronic illness, is generally referred to as sarcopenia.

Other than these problems, The most common cause of muscle imbalance, however, is poor communication between the brain and muscles — neuromuscular imbalance. Most people experience this at various times in their lives. This results in a wide spectrum of problems that range from serious neurological disabilities, such as a stroke patient or those with a brain or spinal cord injury, to those with minor aches and pains. In between are those with varying degrees of physical injuries, chronic pain, and mild to moderate physical disabilities.

With the common feature of these problems being muscle imbalance in varying degrees of severity, they are usually best treated with hands-on rather than exercise therapies.

Beginning in the early 1960s, two health practitioners developed clinical approaches to evaluate and treat muscle imbalance. These would become the foundation for most hands-on muscle therapies that have evolved since.

Dr. Vladimir Janda (1923-2002) and Dr. George Goodheart (1918-2008) influenced generations of health practitioners spanning virtually all disciplines. Both emphasized various assessment and hands-on therapies based on the existence of muscle imbalance. A key feature of both approaches is the use of manual muscle testing, along with posture and gait analysis, to help determine the neuromuscular cause of the imbalance.

Interestingly, Janda theorized that most problems are best corrected by addressing the tight side of muscle imbalance, while Goodheart focusing on the loose (or weak) side. Both practitioners, and the tens of thousands of their followers, continue using these approaches today. Janda incorporated many soft tissue and joint physical therapy techniques, while Goodheart used a variety of approaches, including manipulation, soft-tissue techniques, acupuncture and nutrition. Both also developed many of their own assessment and treatment techniques.

Most hands-on therapies used today that address muscle, ligament, tendon, fascial and other “techniques” with various names and ideas that are often portrayed as “new,” grew directly out of the work of Janda and Goodheart, or were at least influenced by them. When one looks at the many types of practitioners out there today, it can be overwhelming, yet there are actually many common denominators among them. Other than cook-book techniques, where a therapist applies the same or similar technique to everyone they treat, those who rely on assessment tools (such as gait analysis and muscle testing) to determine the best treatment for a given patient, are using something called biofeedback as a common application.

The Biofeedback Fix

During the 1960s, NASA scientists discovered ways for people to consciously influence brain and body health, coining the term biofeedback. In short, all the various assessment tools associated with hands-on therapies, including the works of Janda and Goodheart, are broadly called biofeedback.

Clearly the neuromuscular system is a major network in the body and one that you wish to keep functioning optimally to stay fit and healthy, produce unlimited energy for physical and mental activities and provide support for the skeletal, nervous, circulatory and digestive systems. Keeping the muscles in proper balance not only requires a good aerobic system and strength-building habits, but also proper nutrition and lifestyle choices such as reducing the amount of sitting.