It’s complicated, but science is now showing the sweet stuff is as addictive as many other dangerous substances.

Alcohol and tobacco have long been accepted as harmful substances, as have illicit drugs like cocaine and heroin. Now, for the first time in human history, we are approaching a consensus on adding sugar to this list of dangerous, addictive drugs.

Caffeine, though safer, also is a drug used by millions daily. And many people use over-the-counter and prescription drugs without a thought about their potentially dangerous side-effects.

Which is also the case with sugar, it can be just as dangerous and addicting as any other drug.

The American Psychiatric Association defines addiction as a brain disease associated with substance use disorders, listing 11 criteria for defining it in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Patients must fulfill at least two clinical criteria for a diagnosis of addiction. The model of sugar addiction discussed and referenced in this article meets five of these criteria, such as binge use, craving, withdrawal and others, plus additional behavioral and metabolic attributes observed in animal and human research.

Substance use disorders involve impaired control of consumption such as strong social use, continued abuse despite harm, and pharmacological actions associated with tolerance and withdrawal.

Brain-Body

Sugar addiction is a complicated concept. Biological, psychological, behavioral, nutritional and social factors can all play a role, affecting both brain and body. While there is not yet an official definition or diagnosis of sugar addiction, its immediate and potent effects can act like a drug as defined by the DMS. Side effects include significant metabolic health impairment. And we all know how difficult it is to avoid it.

Moreover, sugar is defined here as sweets, sugar-containing food and beverages, processed carbohydrates such as flour, and other foods that quickly convert to sugar after eating.

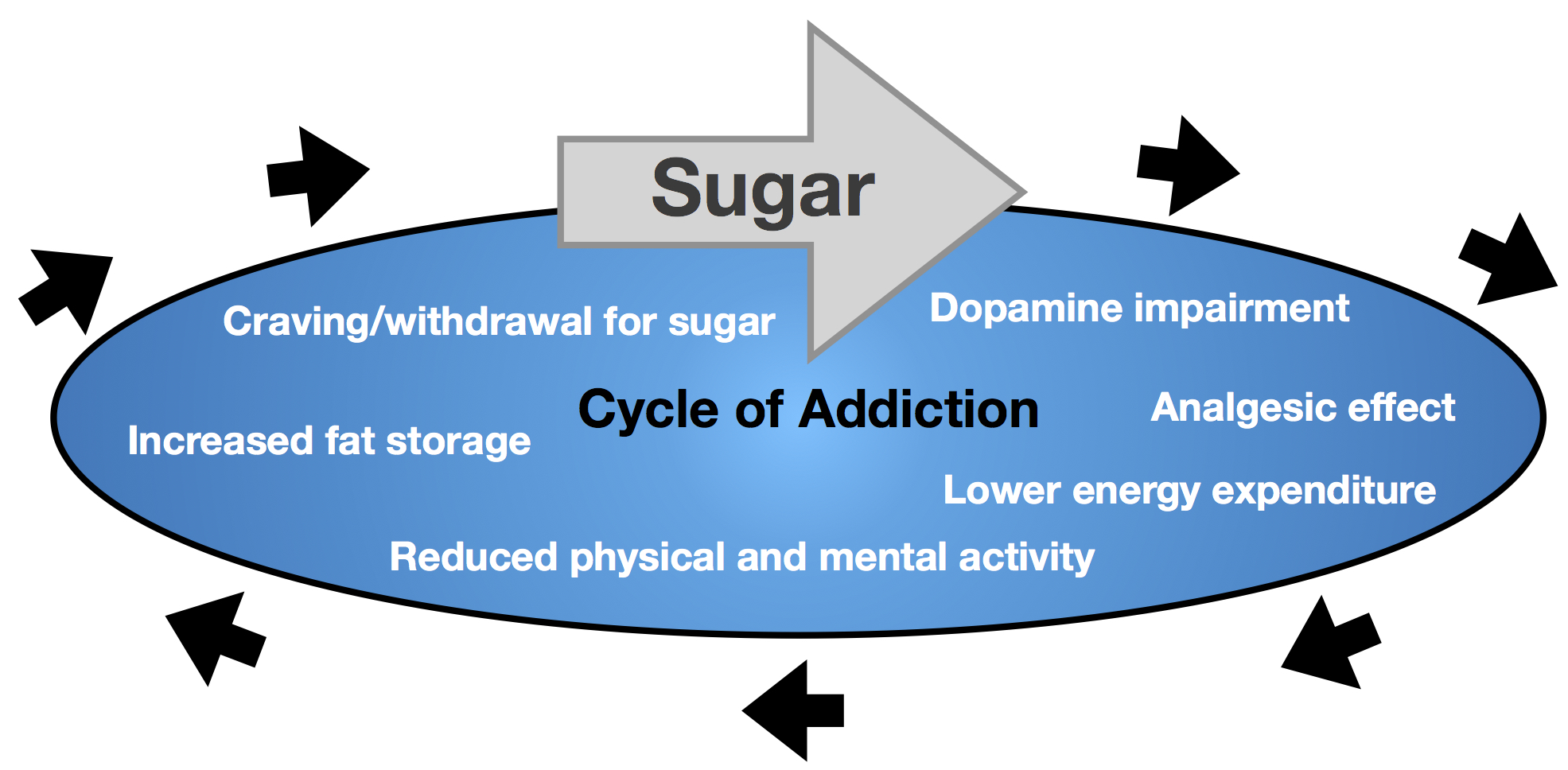

While food addiction has been described and researched for many years, sugar may be the most addictive ingredient in foods. Like drug dependence, sugar disrupts the brain areas of pleasure and self-control. This complex dopamine reward system includes endorphins, endocannabinoids, oxytocin, and opioid-like chemicals playing a key role in the addiction process. This system is activated every time sugar is consumed, making the amount needed for abuse very little. Relatively small amounts of sugar can also have significant and immediate adverse metabolic effects.

Studies show that food addiction is associated with a reward deficiency, as part of the impaired dopamine system, being responsible for, among others, intense cravings and withdrawal symptoms. Carbohydrate intolerance — excess insulin production following carbohydrate intake, insulin resistance, and higher amounts of foods converted to stored fat — is one of the metabolic associations.

Scientists are still unraveling this complex biochemistry, but it’s clinically clear that sugar consumption can adversely affect the dopamine system to maintain the vicious cycle that includes, among others, increased body fat, sugar craving and impaired glucose metabolism.

Sugar also appears to have strong relationships to binge-eating and other disordered eating, including serious conditions like anorexia nervosa. In addition to impaired glucose (diabetes develops at twice the rate in former/current drug addicts) and mental dysfunction, the dopamine mechanism also has strong relationships with poor fat metabolism.

Food addiction is more prevalent in those with excess body fat, typically caused by excess sugar intake. The overfat pandemic now affects most of the world’s population, and is also a primary cause of chronic disease and physical impairment. This would make the prevalence of sugar addiction potentially massive, and it could be among our most serious global issues — regardless of whether we call sugar a drug or not.

The healthcare costs of sugar addiction, which may exceed that of all other drugs combined, is strongly connected to a weakening global economy. In forecasting sugar’s effect in the U.S., Morgan Stanley Research says by 2035, annual economic/GDP growth could decline from about 2.8 percent (2015) to below 0.3 percent.

Addiction Risk

Rather than defining and diagnosing, a key issue about sugar addiction is risk. Many people are at high risk based on specific signs and symptoms. The survey below can help people self-assess their risk for sugar addiction.

Sugar addiction survey

Make an honest appraisal. Check the items that apply to your relationship with sweets, sugar, sugar-containing food and beverage, and processed carbohydrates such as flour.

• Increased craving.

• Impulsive buying or eating.

• Repeated attempts to control use.

• Continued use despite adverse health effects.

• Negative health consequences.

• Regular or daily use.

• Difficulty avoiding.

• Anxiety, depression or withdrawal symptoms when reduced or eliminated.

• Social issues around use.

• Poor tolerance.

• Binge eating.

• Consume when not hungry.

While one or two checked items may refer to lower risk, three or more can indicate higher risk of sugar addiction. (Performing the Two-Week Test can help confirm risk and assess other associated health factors.)

While many human studies lend credibility to the notion of sugar as an addictive drug, animal research supports it too, with parallels in many people:

- Intermittent administration of sugar to rats leads to binge use, similar to when they are given heroin and cocaine, and creates physical impairment of the brain and nervous system associated with addiction.

- In the laboratory, it does not take long to demonstrate the power of cravings in animals fed sugar.

- Sugar, like alcohol, will increase an animal’s consumption following an abstinence period. The same was shown with non-caloric sweeteners, implicating taste’s hedonic power as a key part of addiction.

- In rats, 28 days of sugar consumption, followed by 14 days of deprivation, is very similar to the deprivation of alcohol addiction.

- Sugar follows the model of drug tolerance, the need for more of a substance to obtain similar effects.

- Functional MRI studies show the same addictive behavioral brain response to both sugar and cocaine.

- Craving has been intimately related to high rates of drug relapse, and also demonstrated with sugar.

Addiction Hierarchy

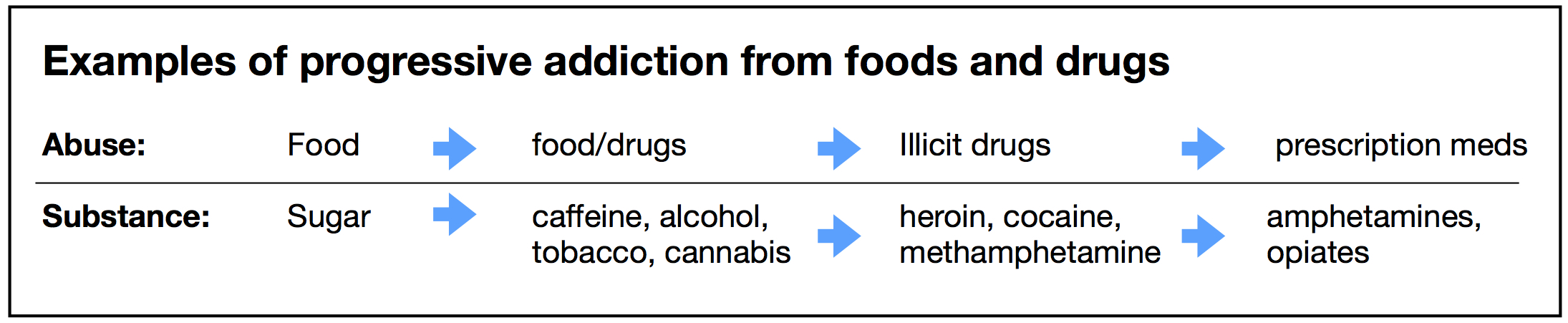

Since the late 1970s, my clinical research with addicted patients demonstrated what I called an addiction hierarchy — abusing certain substances leads to increased use of others. Of the various common drug-dependent substances, from alcohol and caffeine to tobacco and illicit substances, when individuals regularly consumed two or more, sugar appeared as the primary addiction. And, when treatment was directed at eliminating sugar, eventually addressing other addictions was more successful. In addition, without sugar consumption addiction itself appeared significantly reduced, and eventually eliminated.

Over time, other research demonstrated cross-sensitization, the abuse of one drug leading to abuse of another. This typically begins with sugar, leading to “soft” drugs like caffeine and cannabis, to alcohol and tobacco, and sometimes to illicit and prescription drug abuse. Along the way, sugar abuse worsens. This vicious cycle is shown below.

Other research results also support an addiction hierarchy:

- Opiate use increases the desire for sugar consumption.

- Once off heroin, methadone patients develop strong desires for sweets and can increase sugar intake significantly (in one study, sugar increased to 31 percent of dietary calories).

- Sugar-dependent rats show cross-sensitization to drugs of abuse and the other way around.

- Sugar promotes drug abuse behavior — sugar-dependent rats forced to abstain intensified their intake of alcohol, so sugar seems to act as a gateway to alcohol use.

- Abstinence of one drug increased addiction sensitivity in the brain, which can be satisfied by other drugs — in alcohol abstinence, this may include sugar, caffeine, tobacco or combinations.

As such, a successful reduction, control or the elimination of addiction itself may not occur while sugar maintains that addiction. Eliminating sugar may therefore be the most effective first step in treating any addiction.

Other relevant studies addressing sugar addiction include:

- Addiction transfer to the newborn due to maternal exposure of sugar can influence neurodevelopment.

- Maternal sugar intake can impair hormones, especially insulin, impairing fetal metabolism.

- About 20 percent of U.S. adults may be food-addicted, the same number of those addicted to tobacco, and to alcohol. However, this was the mean; prevalence of food addiction may be as high as 56 percent. (This study used obesity in the analysis, which may miss the much higher numbers of people who are overfat, about 90 percent of Western populations.)

- The sugar-drug addiction similarity is also related to the neurobiology of relapse, including persistent drug seeking, increased motivation to obtain the drug, and reverting to bad habits under other lifestyle stressors or exposure to food cues in ads, shopping and social events. For example, it’s not easy being around smokers or in a bar if you’ve recently given up cigarettes or alcohol.

Sedation, Withdrawal and Craving

Sugar consumption can induce a sedative feeling due to the brain’s production of opioid-like chemicals. This drug-like analgesic effect — the feeling of sleepiness after a meal or snack containing sugar or other refined carbohydrates is a common symptom. In laboratory animals, sugar sedation is powerful enough to inhibit pain. Long recognized in humans, it is the basis for the use of sugar in babies to relieve crying and other pain-related sensations, including its use as an analgesic for minor surgery. At any age, sugar is powerful enough to amplify the analgesic effects of morphine and other opiate pain-relieving drugs, including anesthesia.

As a separate symptom, sugar withdrawal has been recently shown to be analogous to opiate withdrawal and its associated anxiety and depression. These are common complaints by those performing the Two-Week Test, where the primary dietary adjustment is the acute reduction of sugar.

These effects, which include artificial/non-caloric sweeteners, can impair both physical and mental activity.

- Physically, reduced movement, including the potential lost desire to exercise, can reduce metabolic energy expenditure leading to reduced fat-burning and increased fat storage.

- Mentally, it can impair learning, motivation, focus, creativity, and memory.

A craving is a strong desire for a drug or sugar, engages reward, emotion, conscious control, memory and mood, and can be triggered by taste, smell, photos and other sensations, and lead to impulse eating. As a powerful symptom, craving is intimately related to high rates of relapse. And, sugar craving is the symptom that makes marketing junk food a much easier task, which advertisers have long known and used to influence eating behavior.

While sugar addiction does not perfectly fit into models of other substance abuse, there is more than adequate evidence to classify sugar as a drug. It is easily abused, significantly harmful to health, has a high risk for dependency, and is associated with craving and withdrawal. That it is readily available and inexpensive fuels its use by most people in the world.

With increasing scientific research, an even better sugar-addiction model will develop. As a consensus, it would easily be the most addicted substance worldwide, immediately instigate a massive global public health dilemma, and, hopefully, a productive response. But why wait?

References

Ahmed SH, et al. Sugar addiction: pushing the drug-sugar analogy to the limit. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(4). doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328361c8b8.

Avena NM, et al. Evidence for sugar addiction: Behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008; 32(1). doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.019.

Hasin DS, et al. DSM-5 Criteria for Substance Use Disorders: Recommendations and Rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013; 170(8). doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782.

Kalon E, et al. Psychological and Neurobiological Correlates of Food Addiction. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2016; 129. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2016.06.003.

Kolarzyk E, et al. Assessment of daily nutrition ratios of opiate-dependent persons before and after 4 years of methadone maintenance treatment. Przegl Lek. 2005;62(6).

Lundqvist MH, et al. Is the Brain a Key Player in Glucose Regulation and Development of Type 2 Diabetes? Front Physiol. 2019; 10. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00457.

Lu H, et al. Abstinence from Cocaine and Sucrose Self-Administration Reveals Altered Mesocorticolimbic Circuit Connectivity by Resting State MRI. Brain Connect. 2014; 4(7). doi: 10.1089/brain.2014.0264.

Mysels DJ, Sullivan MA. The relationship between opioid and sugar intake: Review of evidence and clinical applications. J Opioid Manag. 2010; 6(6).

Saha TD, et al. Analyses Related to the Development of DSM-5 Criteria for Substance Use Related Disorders: Toward Amphetamine, Cocaine and Prescription Drug Use Disorder Continua Using Item Response Theory. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012; 122(1-2). doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.004.

Veldhuizen MG, et al. Integration of sweet taste and metabolism determines carbohydrate reward. Curr Biol. 2017; 27(16). doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.07.018.

Wiss DA, et al. Sugar Addiction: From Evolution to Revolution. Front Psychiatry. 2018; 9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00545.